In May, Dong Nguyen uploaded a new game to the iOS App Store, just one of hundreds of apps added daily to Apple’s iTunes marketplace. In that sense, it was just a game. But it would turn out to be anything but.

Nguyen had been developing a simple game in which players tapped the screen to control a funny-looking bird, but it needed a simple name. He called it “Flap Flap” until he noticed another app with the same title. Luckily, developing and updating games on the App Store is a very fast and iterative process, so he was able to quickly change the name to Flappy Bird.

You may have heard of it before.

Nguyen’s game became one of those viral success stories you hear about every now and then as the next Angry Birds, the next Temple Run. A few months after its release, Flappy Bird shot to the top of the charts, attracting even more players, which only made it more popular and attracted even more players. At its height, millions of people downloaded Flappy Bird, and Nguyen made $50,000 a day from the pop-up ads that appeared while he played.

But he was also constantly bombarded with messages, insults, interview requests and even death threats. Nguyen decided last weekend that it wasn’t for him. He stopped talking to anyone and removed Flappy Bird from the App Store. Like the little bird he created, he soared for a moment before coming down hard.

This is what happened.

Get Ready!

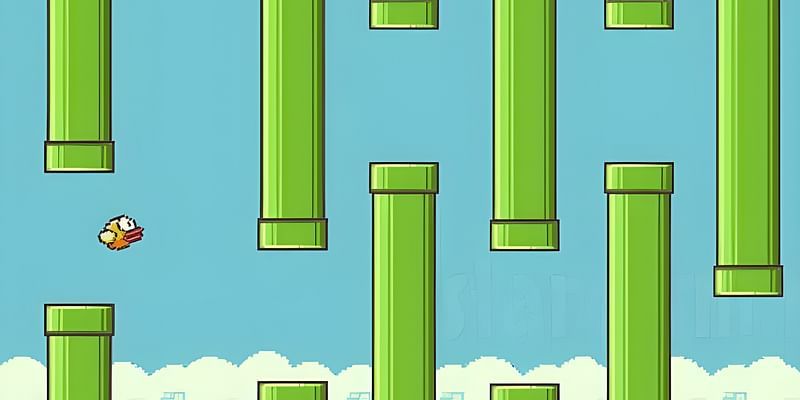

Flappy Bird was similar to other games Nguyen had released for mobile devices, such as Shuriken Block and Super Ball Juggling. The graphics were a nice homage to retro-style sprite art, and the gameplay was very simple, with games lasting only a few seconds at higher difficulty levels.

The concept almost seemed too simple: tap the screen to jump up, release to dive down, and navigate gaps in a series of green tubes that were clearly modeled after those in the Super Mario series. The gaps were appealingly wide, several times the height of the bird. But the bird moved so quickly, swooping up and down, that getting through the gaps without falling was a major challenge. You only get one point for each pipe you clear, so your high score will probably be in single digits, or maybe even zero.

For a few months, Flappy Bird performed pretty much the same as Nguyen’s other games, which means almost no one had ever heard of it. In late October, he released a small update that fixed a few bugs. A few days later, something changed. Someone other than Nguyen sent the first tweet about the game.

“Fuck Flappy Bird” was the full sentence. The

game was tedious but addictive, and because a heart broken is a heart broken, players who found it wanted to vent their anger. Throughout November, Flappy Bird slowly gained new users. Reviews slowly grew from one a day, then three, then twenty. Its growth seemed entirely based on word of mouth, as players expressed their love or hate for Flappy Bird. Nguyen engaged with his growing fanbase through Twitter and even promised to port the game to Android.

As of the end of December, Flappy Bird was struggling to reach number 80 on the US App Store’s “Free Games” chart. It was a steep climb from there: its popularity began to soar as more and more users complained on Twitter about the brutal difficulty. Nguyen was all the more pleased when Flappy Bird entered the top 40 most downloaded free iPhone games. It then made it into the top 10.

On January 17th, it was #1 among the most popular free apps in the world.

Fans started writing hilarious 5-star reviews claiming that the game was ruining their lives. “I’m sitting in the bathtub writing this review, warning you not to download it,” one wrote. “My family doesn’t dare go in.” My brother hasn’t showered in a month.”

“All it takes is to see the words ‘Flappy Bird’ and 19 hours later you’ll find your fingers are bleeding, your screen is cracked and your eyes are taped open.” , “Insomnia and paranoia set in and you’re so determined to get the devil’s bird through the impenetrable gates that you’re willing to sacrifice every part of your body except your thumb if it helps you achieve a high score,” another wrote.

Then I found out about Flappy Bird and I was shocked, thinking, “What kind of low-budget game is this that uses all the graphics from Super Mario? Why has it become so popular?” I downloaded it and played a few rounds. It was my fault.

I kept playing. I was always angry that I couldn’t get more than 10 points. I was excited. I had to talk to this guy. On January 24, I emailed Nguyen requesting an interview.

The next day, I got a response. “Wow, I’m honored to have the opportunity to be interviewed by WIRED,” he wrote. “I love your magazine and would love to do that.” We arranged to meet on Skype.

When it came time to call, Nguyen said he’d rather chat via text message. We answered some basic questions – his name is Dong Nguyen, he’s been making games for four years, and he lives in Hanoi – but the back and forth took so long that I asked him if he could answer my questions in his free time. I’d like to email them to me. It was the middle of the night in Hanoi and I was tired, so he readily agreed.

In the evening, we said our goodbyes, and that was the last I heard from Dong Nguyen.

I wasn’t the only one asking questions about Flappy Bird. The annoying game garnered more diverse responses and passionate debate than any other iOS game in recent memory. CNN struggled to explain why Flappy Bird was so addictive. Game critics said the game proves that no one really knows what players want. CNET called it “the embodiment of our descent into insanity.”

Throughout all of this, Nguyen found himself increasingly in the spotlight. At first, he seemed to handle the attention with a cheerful and calm demeanor. He endlessly tweeted with his fans and wasn’t fazed when people sent him less-than-kind messages. “I’ve gotten a lot of mean tweets but I’m getting used to it,” he wrote in late January.

Soaring

But the negative attention given to Flappy Bird soon overshadowed the positive comments. Flappy Bird’s continued hold on the top spot in the App Store led to increasingly vicious online harassment, some of which was racist in nature. There were even death threats. As hundreds of people continued to send him tweets saying they hated the game and hated Nguyen for creating it, his confidence began to turn to self-doubt. “And now I don’t know if that’s good or bad,” he wrote on Twitter. Gradually, even banal remarks began to wear him down. He apologized profusely to fans who were frustrated by the slow release of Flappy Bird for Windows Phone. “I’m really sorry I can’t keep my promise, but I’m working hard,” he wrote. “I have a lot going on right now.”

Following the torrent of criticism and negativity that rained down on Nguyen, indie game designer Terry Cavanagh defended Nguyen on February 5th. “Flappy Bird is kind of cool, but why is it raining so much? I’m upset,” he tweeted.

Cavanagh’s game Super Hexagon is another iTunes success story, and he was one of the first people Nguyen followed on Twitter. As it turns out, Nguyen follows a lot of indie game designers. From his tweets and interviews, it is clear that he wants to pursue a career as a game designer. He has even stated that he doesn’t want a publicist between him and his fans because “if I have a publicist, I’m not an indie game developer anymore.”

Coverage from the media, especially gaming websites, has also been negative.

After The Verge revealed how much Nguyen was making from advertising Flappy Bird, Kotaku published an article on February 6th with the headline “Flappy Bird is Making $50,000 a Day from Ripping Art.” In it, Nguyen was accused of copying Nintendo sprites and pasting them into the game. Nguyen responded that he never copied the art and drew it all himself. This sparked a new wave of offensive comments, which eventually led Kotaku to retract the article and apologize.

IGN wrote on February 8 that “Flappy Bird is not a good video game… and probably not even a fun game,” calling it “completely artless.”

“The press is overstating the success of my game,” Nguyen tweeted in early February. “That’s something I never want. Leave me alone.”

While the gaming press rushed to criticize Flappy Bird’s gameplay mechanics, other app developers tried to spread the idea that Flappy Bird’s success was illegitimate. They believed that Nguyen was using “bots” (virtual iOS devices used to increase app downloads and artificially boost charts) to play the game, violating Apple’s terms of service.

“Sorry to say this, but it really does look like bot activity,” app developer Carter Thomas wrote on Jan. 31, adding that he “obviously can’t prove it.”

In fact, the only “proof” of cheating that Thomas could offer was Flappy Bird’s meteoric rise up the App Store’s Top 100 charts. But that didn’t stop many from assuming the worst and accusing Nguyen of cheating, a charge he has denied.

Ian Bogost, who has written about Flappy Bird for The Atlantic, told WIRED there’s really no way to determine whether Nguyen cheated to get his game to the top of the charts.

“Who cares?” Bogost said. “What’s interesting is how desperate the game developers are to believe this is cheating. They can’t stand the idea that something like this actually exists.”

Falling

As the week progressed, Nguyen’s confidence first grew shaky, then depressed. “I would say Flappy Bird is my success,” he wrote on Twitter. “But it’s also ruining my simple life so now I hate it.”

“Fine,” someone replied. “Everyone else hates it too.”

“Hahaha,” Nguyen tweeted.

By Saturday, Nguyen was no longer laughing. He had decided to take Flappy Bird off the market.

“Sorry to all Flappy Bird users, I will be delisting Flappy Bird within 22 hours. I can’t take this anymore,” he wrote. This sparked a rush to download the game before it disappeared forever. On Sunday night, Nguyen made good on his threat: Flappy Bird was gone. That drew even more attention and harassment to Nguyen. “If you remove Flappy Bird I will kill myself,” one player wrote, attaching a disturbing photo of a woman with a gun in her mouth.

Critics of Flappy Bird wasted no time spinning conspiracy theories. Some suspected that Nintendo had threatened Nguyen with a lawsuit because of the similarity between Super Mario’s green pipes and Flappy Bird’s. A Nintendo representative denied these allegations to The Wall Street Journal.

People couldn’t understand why Nguyen would remove an app that made him so much money. To be fair, Flappy Bird is probably still making money, as Apple iAds continue to appear on the more than 50 million devices that have the game installed. Nguyen also left his other two mobile games on the mobile marketplace, but the global attention given to Flappy Bird boosted it up the download charts.

So the answer to the question of why Nguyen stopped playing and retired may simply be that he really wants people to leave him alone and stop playing Flappy Bird.

The Me-too app is rushing to fill the gap. On Tuesday, the four most popular free apps on iOS were Fly Birdie, Splashy Fish, Ironpants and Flappy Bee, all Flappy Bird clones.

If Nguyen were to return to game development, he would have many supporters in the gaming community. A group of indie developers is even hosting a game jam in his honor, with the message: “Have fun, be helpful. Hate should never win.” Cavanagh, the designer of SuperHexagon, was there. “I don’t know if a game jam makes sense here, but I’m frustrated and want to do something,” he wrote.

Like other people who become famous overnight, Dong Nguyen has learned that success is like a game of Flappy Bird: The forces that pull you down are just as strong as the forces that pull you up, and each of them can make you crash sooner than you expect.

Leave a Reply