One of the best reasons to own a SNES in 1993 was the format-exclusive Secret of Mana, which was first released 30 years ago this week, on August 6th.

Secret of Mana – known in Japan as Secret of Mana 2 – is one of the best RPGs of all time, and no one could afford a piece of software that felt like a microcosm of the kinds of games found on rival consoles from the likes of Sega and NEC/Hudson. And yet how ironic that the existence of this game was what would prove decisive in the demise of Nintendo as a dominant player in the home console market, both domestically and internationally, for the foreseeable future.

Secret of Mana was the work of one of the most respected studios of the 1990s, Squaresoft (now Square Enix), developer of Japan’s most popular and bestselling role-playing game genre, and Square would not release games for anyone else. Nintendo in 1993. The brutal experience of developing Secret of Mana would change everything forever.

A Mana in the works

The game is a great example of an action RPG, where the player directly controls their character in real-time combat with lots of button mashing, rather than through cumbersome turn-based combat menus like most other RPGs. Secret of Mana tells the story of three heroes (a trio of unnamed boys, girls, and magical water goblins in the US and European versions) and their mission to stop an evil empire from subjugating them by harnessing the divine power of the mysterious Mana Tree. Conquer the world with the help of a steampunk-inspired flying fortress.

The graphics are still incredibly appealing, with excellent transparency effects, a perfectly chosen pastel color palette, and captivating Water Goblin creations. The armored Kid Goblins and Mashbooms (living mushroom people with hearts on their mushroom caps) who adorably blow bubbles when you approach them before waking you up are so cute that you can almost not bear to stab them for experience points – but that’s the role – you have to, because playing the game works. Flying around a Pilotwing-esque map with a big, hairy white dragon Flammie (similar to the beast from The Neverending Story) using

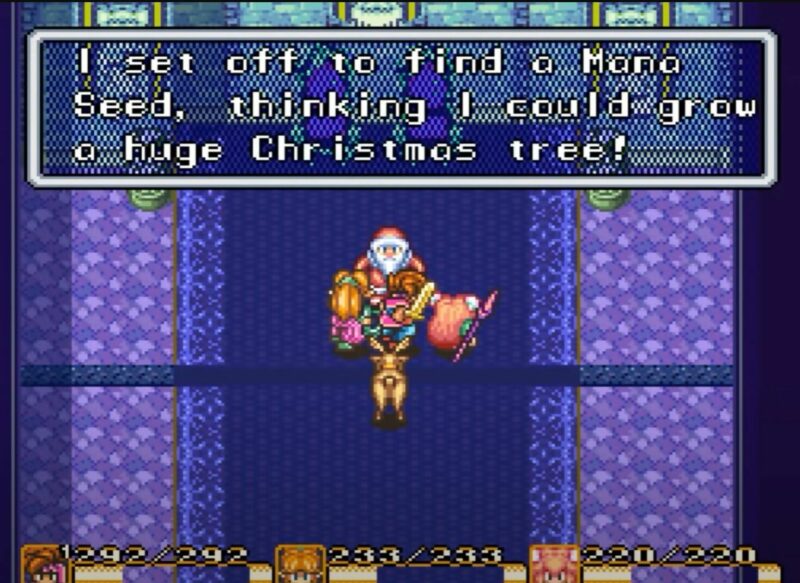

Mode 7 was also technically impressive. Even the menu system, designed around the now-imitated “ring command” mechanic, was a work of design genius, while the ability for three players to separately super multi-tap to control a trio of warriors seemed novel at the time. Plus, not every game has a title screen that samples Santa Claus or a whale song. (Sound-wise, Kikuta Hiroki’s memorable soundtrack is one of the best on the SNES, alongside Super Castlevania IV and Actraiser.)

Secret of Mana is also a very long game, offering a lot of replay value, and the difficult story of the game’s creation is just as long.

Mana from Heaven, development Hell

From the outside everything looked good. Secret of Mana was the second best selling game in Japan in 1993, selling over a million copies and staying in the top ten of the US SNES charts from 1993 to the following year. In Europe, where Square had almost no presence, the game was published directly by Nintendo themselves, giving most 16-bit gamers their first experience of both role-playing games and Square’s products themselves, further strengthening and cementing the bond between Square and Nintendo. All this shows how appearances can often be deceiving.

The secrets of Mana’s development history are quite complicated. The first title in the series, known as Seiken Densetsu (or “Legend of the Holy Sword”) in Japan, was never published. Seiken Densetsu: The Rise of Excalibur was meant to be an RPG of unprecedented scale and scope, released for the Famicom Disk System (FDS), a Japan-exclusive floppy disk-based media for the NES. The big concept here is the size of the game; it would take up an incredible five discs, presumably telling a story that would span multiple generations, one on each disc.

The game was scheduled for release in April 1987, but was repeatedly delayed and appears to have been pure vaporware. There are some screenshots, but they seem to be mock-ups of advertisements that Square foolishly sent to potential buyers.

It is likely that the creation of Excalibur never existed beyond paper plans, an overly ambitious project that executives were happy to abandon in the face of Square’s imminent bankruptcy and the FDS’s own declining sales. In October 1987, Square sent refund letters, politely suggesting that disappointed pre-purchasers use their money instead to buy the original software for the NES, Final Fantasy, a smash hit that changed the fate of the entire company.

And in 1991, a good little ARPG with wonderfully squeaky music called Seiken Densetsu appeared on Nintendo’s Game Boy handheld, marking the true beginning of the Mana series. Confusingly, it was renamed Final Fantasy Adventure in the US and Mystic Quest in Europe.

Some characters from Final Fantasy games come from the same original development team, so some characters, notably Chocobos and Moogles, appear in Secret of Mana titles. Secret of Mana II itself started out as Final Fantasy IV but eventually became something else, initially codenamed Chrono Trigger during development… but it wasn’t the RPG that would later be released as Chrono Trigger by Square in 1995. It was a completely different game for the SNES. Or not?

Now you CD it, now you don’t

The fateful development story of FDS’s first title, Emergence of Excalibur, eerily paralleled that of Secret of Mana II, originally planned as the flagship starter title for Nintendo’s upcoming SNES CD device and set to be released in 1993 or 1994.

Cartridge storage was a long-standing point of contention between Square and Nintendo during the 16-bit era, with Nintendo charging a very high price for each megabyte of extra storage on the cartridge, resulting in some of Square’s long-form, story-driven RPGs being released on cartridges that ultimately cost the equivalent of over $100 in Japan, so never left their homeland. This fate later befell Secret of Mana III, which saw the light of day in the West in 2019 as part of the Collection of Mana port for the Switch, now translated as Trials of Mana. Japanese is linguistically more compact, so the vast amount of English text obviously wouldn’t fit on the original cartridge.

Square’s memory resources were so stretched during the SNES era that they actually named Chrono Trigger’s protagonist “Crono” instead of “Chrono” because consistently omitting the extra “h” actually made a difference to all of the game’s text whether it would fit on a 32MB cartridge (which was huge for the time). Storing the letter “h” was no longer an issue with the new CD-ROM format of the 1990s, which allowed for around 650 MB to be stored on each disc at no extra cost.

Thus, Secret of Mana was originally planned to be a gigantic title, reminiscent of the never-produced The Rise of Excalibur, involving time travel and exploring the fate of the Kingdom of Mana over several generations. The player was originally meant to be faced with a series of in-game decisions that would lead to several different future paths, and multiple playthroughs were required to see all of the game’s endings.

However, the SNES CD was eventually canceled by Nintendo, after which Square’s desperate development team tried to abandon the project altogether. Square executives refused, forcing them to re-edit the game in a more compact form and release it anyway in order not to waste resources. As a result, nearly half the content was cut, with Secret of Mana estimated to be only 60 percent of the length it was planned to be.

So what happened to the missing 40 percent? Well, some of it was re-edited and turned into the actual game we now know as Chrono Trigger, a time-travel RPG that features actual branching depending on the decisions the player makes in the game. The main heroes of both role-playing games are two spiky-haired guys who visually may look like long-lost twin brothers, and in some ways, they really were.

The secrets of Secret

From the SNES owner’s point of view, this was probably the best outcome: Nintendo fans got two great, independent games instead of just one that could be bloated. The planned feature-length, Chrono Trigger-style Secret of Mana wouldn’t have been Secret of Mana as we know it, and it wouldn’t have necessarily been as good.

But the forced downsizing of the game also had negative consequences: some crowded screen sections and boss fights suffer from serious graphical glitches, and the AI of the two computer-controlled heroes frequently goes haywire and gets stuck in the scenery when playing alone, sometimes requiring a reset. Traces of the planned multiple choice paths also get caught in the code, and talking to NPCs in the wrong order can crash the game.

This is why fans have been scouring Secret of Mana for hidden remnants of uncut content. Should a passageway that leads to nowhere lead to an entirely new area, or is it intentionally designed to be a dead end to confuse the player, like many standard RPG mazes? The strangest thing is a big spinning round thing called a “Merry-go-round” that can be seen on the Mode 7 map from the back of a Flammie near Empire Northtown. Whatever it is, once you land it’s nowhere to be seen. What is it? No one knows, but the best guess is that it’s a cutout item accidentally left on the map.

Or it could be an inside joke by the developers. In the 90s The Square enjoyed confusing players with weird little Easter eggs. They were known to insert hidden faces into the backgrounds of some of their titles, leading some to theorize that the company was incorporating secret satanic messages to corrupt the minds of innocent children. In Secret of Mana, the famous “Face On Mars” optical illusion from an old NASA photo can also be seen on the map screen. Perhaps the “carousel” is actually a round flying saucer on Mars?

Another Easter egg that somehow slipped past Nintendo’s strict censors in the 1990s was an animation involving a Mystic Book enemy. A ghostly flying spell book flips through the air, casting a spell that matches the page it lands on. On rare occasions, a pornographic image of a naked blonde woman’s midsection would appear.

A very CD business

However, what was good for players was not good for developers. Their frustrating experience with Secret of Mana played a key role in Square’s decision to release next-generation games on platforms that used CDs as a format. This marked Square’s inevitable (and bitter) parting of ways with Nintendo.

Nintendo’s president at the time, Hiroshi Yamauchi, disliked CDs because they were susceptible to piracy. It was also felt that they took too long to load data compared to cassettes, which was understandable. Thus, when the N64 finally came out in 1996, it was the only next-generation device that still used the old physical storage format.

This decision had a lasting impact on Nintendo’s future. Sony was one of the original co-developers of the original SNES-CD, and used the cancellation of the add-on as motivation to develop its own CD-based console, the PlayStation (the originally planned name for the SNES-CD itself). It is used as the logo on the only remaining prototype, which sold in 2020 for $360,000).

In addition to larger storage capacity, CDs offered several valuable business advantages over third-party carts. They were cheaper to produce and faster to print, making it less likely that publishers would have to fill their warehouses with unsold books in the event of a costly flop, or be unable to ship stock to stores quickly in the event of an unexpected hit.

Sony also offered publishers much more favorable licensing terms than Nintendo, which ultimately led to Square announcing in 1996 that it would hand development over entirely to Sony, sparking a bitter feud between the two once allied companies. Until the middle of the following GameCube generation, Nintendo consoles were completely devoid of Square titles.

Final Fantasy games were so popular in Japan that Sony Square also offered better terms than usual, seemingly making the perfect deal. When Enix followed suit shortly thereafter, bringing its equally popular Dragon Quest series to PlayStation instead of the N64, Sony firmly established its grip on the Japanese domestic market. Since Japan was the undisputed center of the gaming world in the mid-1990s, this also meant inevitable global dominance of Sony devices over Nintendo devices.

Nintendo could have avoided all of this. If the console giant had listened more sympathetically to Square’s problems during the development of Secret of Mana and Chrono Trigger, the mistake of eschewing CDs in favor of cassettes could have been avoided. Given that Nintendo’s 64-bit machines were far more powerful in almost every other respect than Sony’s 32-bit competitors, one has to assume that Square and Enix would have stuck with them rather than defecting to Sony, who left Nintendo after the NES. The SNES won the console wars three consecutive generations.

So the biggest Chrono Trigger-style alternate ending, hidden in Secret of Mana’s sloppily edited code, is actually a complete swap between Nintendo and Sony’s 32-bit and 64-bit futures. Secret of Mana is actually Sliding Doors: The Video Game.

Leave a Reply