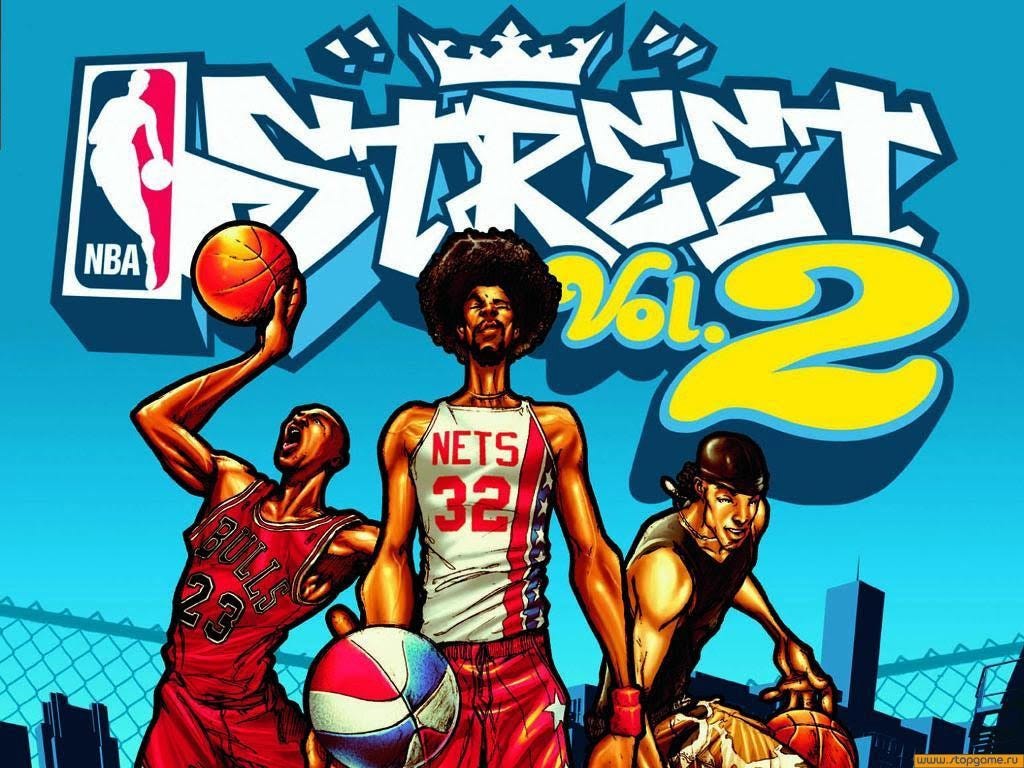

It’s been a decade and a half since Electronic Arts released its last truly great basketball video game, NBA Street Vol. 2. Fifteen years later, the game’s style and spirit (and, of course, its soundtrack) remain unmatched. Sure, new technology has allowed for ultra-realistic graphics and gameplay like NBA 2K, but realism wasn’t the goal of Street Vol. 2. It portrayed basketball not just as a sport played in identical, sterile arenas across the country, but as a vital civic institution with its own history, music and sense of place. It was a tribute to basketball as a spectacle, as an art form and as a cultural epicenter.

It was a lot of fun, too.

The gameplay was fluid, dynamic and fast-paced, sprinting for 21 points, three-on-three down to the second and third every game on streetball courts across the country. Vol. 2, rather than faithfully recreating a regular game of basketball, they wanted to recreate the everyday spirit of the sport. There were no fouls, no outs. (There was goaltending.) Going for a dunk, players briefly assumed the gravity of the moon, gliding toward the basket like ballerinas, like Jumpman.

Energizing every moment of the game were not just the groans of the players and the clang of the ball cutting through the steel net, but the sounds that could be heard from outside the field. A few spectators yelled “oohs” and “ohhs” from the sidelines. A selection of ’90s and early 2000s hip-hop — individual packages of Dilatated Peoples, MC Lyte, Erick Sermon, Redman, and Just Blaze beats — thumps at block party volume. Real-life streetball MC Bobbit Garcia, aka DJ Cucumber Slice, acts as a one-man commentary team/hype man, breaking every block (“Defend the nest!”), every theft (“Oh, hey, money!”) and cheering for everyone who gets behind the wheel (“Do you need a straw for your shake?”). The

controller’s gentle learning curve and responsive feel are beginner-friendly. Vol. 2 didn’t believe in delayed gratification. It didn’t take much practice to outrun your opponents halfway through Guatemala or outrun them like Blake Griffin did with Kendrick Perkins. The game inspires you to drive to the hole or acrobatically fly to the basket and utilize the dozens of tricks and dunks at your disposal to earn enough trick points and give your opponent a soul-shattering Game Breaker. Once you trigger a Game Breaker, you are no longer an actor but a spectator, experiencing an out-of-body experience and witnessing your own legend unfold in real time. A moment of nostalgia – that was Vol.2 in a nutshell. The past isn’t over. It’s not over yet.

To celebrate the 15th anniversary of NBA Street Vol. 2, GQ spoke with an unlikely bunch of successes: a team of Canadian “hockey players” who came to the project with little to no knowledge of streetball. They did their homework, became “devout disciples of the religion of street basketball,” and paid homage to the fertile mecca of Rucker Park on 155th Street in Harlem.

Open Court

NBA Street Vol. 2 was developed over two years at EA’s Vancouver campus by a team led by producer Will Moselle. Moselle, a veteran of five NBA Live games and a holdover from the original, since-disbanded NBA Street team, took on the challenge of a clean slate and assembled a team of people familiar with production formulas and traditions but largely unfamiliar with sports video games. Some had never worked on a video game before. In search of a new art director, Moselle landed on Kirk Gibbons, a “zen master” who once won a national championship with the University of California, Santa Barbara surfing team and developed several digital basketball products for Nike. Members of Vol. The two began to study streetball and hip-hop history religiously. They pored over books, documentaries, and AND1 mixtapes, and visited New York’s most famous streetball spots. “We immersed ourselves in the culture as deeply as a white guy on the west coast of Canada,” says Adam Myhill, the game’s technical director. “I was obsessed with Jadakiss and Nas at the time,” says Gibbons. “I joke that I’m a method art director, but I listened to hip-hop all the time while I was making the game.” – A 30-minute spot that first aired during the 2001 NBA All-Star Game. In the commercial, unknown streetball players and NBA stars like Lamar Odom, Jason Williams, and Baron Davis take turns dancing under the spotlights of a pitch-black arena, moving the ball like a yo-yo. “We were blown away by how much the creative (directors) focused on the players’ skills and movements,” Moselle said. “There was no narration, no special effects, no acting — just pure basketball and streetball talent. This was a live version of our game. We wanted the in-game movements to speak for themselves, and for players to see, feel and simply be impressed by the talent on display.” We wanted to speak to someone who could capture the essence of that skill and talent. ”

With the help of Glenn Chin, head of marketing at EA Canada, Moselle tracked down the mastermind behind the Nike Freestyle commercial: Jimmy Smith, creative director at ad agency Wieden+Kennedy. Moselle invited him to work on Vol. 2.

“I still remember his phone call,” Smith said. “I said, ‘Should I do a commercial?’ And he said, ‘No!’ I want you to help me make an actual video game!’ And I said, ‘Hey, I’m a pinball guy. My sons play, and I’m a pinball player.’ And he said, ‘No, hey, we want the culture.’ We want everything you bring to the Nike job.” We want to put that in an actual video game. We want it to be authentic. And I said, ‘Yeah, you can do that. I could do that all day.’”

Voice of the Court

Smith has worked on Nike’s streetball advertising campaigns for nearly a decade. Vol. 2 gave him the opportunity to apply his streetball expertise to a broader medium than advertising: video games, where, through a process of “collaboration,” he helped select and develop the game’s music, courts and fictional streetball players. But his greatest contribution was recruiting Bobbit Garcia to be the voice of the game.

“Bobbit is a legend,” Smith said.

After working on dozens of Nike commercials since the mid-’90s, Garcia flew to the EA campus for a marathon recording session.

“They booked me, I flew to Vancouver, stayed there for a whole week, and gave me pages and pages of scripts,” Garcia recalled. “Pages and pages of scripts. And I looked at them and I was like, ‘Oh, we don’t talk like that, so we need to allow you to improvise here.’ They said, ‘Oh, no leads, totally freaking out.’

Garcia was the man. Uniquely situated at the intersection of hip-hop and streetball, he is a DJ and baller himself, co-host of the famous hip-hop radio show Stretch and Bobbito, and a commentator for New York streetball games since 1982.

“I sat on the plane for eight hours, five days in a row, screaming my heart out,” he said. “It was a big hit within the first 15 minutes, because the boys were out there laughing. We just made up some nonsense like, ‘It’s a slice of pizza with no crust!’ whatever, because their argument was, ‘Hey, people are going to play this for hours, so we need to come up with 40 different ways to say the word ‘dunk.’ Otherwise it’s going to be repetitive, I thought. ‘There are so many ways to say, ‘Oh my God, I came from the depths!’”

Sometimes they went outside to play a game of horse, and Bobbitt, a walking streetball encyclopedia, helped the Vol. 2 team identify the names and meanings of various moves and entertained them with stories from the streetball canon and old times.

Smith has worked on Nike’s streetball advertising campaigns for nearly a decade. Vol. 2 gave him the opportunity to apply his streetball expertise to a broader medium than advertising: video games, where, through a process of “collaboration,” he helped select and develop the game’s music, courts and fictional streetball players. But his greatest contribution was recruiting Bobbit Garcia to be the voice of the game.

“Bobbit is a legend,” Smith said.

After working on dozens of Nike commercials since the mid-’90s, Garcia flew to the EA campus for a marathon recording session.

“They booked me, I flew to Vancouver, stayed there for a whole week, and gave me pages and pages of scripts,” Garcia recalled. “Pages and pages of scripts. And I looked at them and I was like, ‘Oh, we don’t talk like that, so we need to allow you to improvise here.’ They said, ‘Oh, no leads, totally freaking out.’

Garcia was the man. Uniquely situated at the intersection of hip-hop and streetball, he is a DJ and baller himself, co-host of the famous hip-hop radio show Stretch and Bobbito, and a commentator for New York streetball games since 1982.

“I sat on the plane for eight hours, five days in a row, screaming my heart out,” he said. “It was a big hit within the first 15 minutes, because the boys were out there laughing. We just made up some nonsense like, ‘It’s a slice of pizza with no crust!’ whatever, because their argument was, ‘Hey, people are going to play this for hours, so we need to come up with 40 different ways to say the word ‘dunk.’ Otherwise it’s going to be repetitive, I thought. ‘There are so many ways to say, ‘Oh my God, I came from the depths!’”

Sometimes they went outside to play a game of horse, and Bobbitt, a walking streetball encyclopedia, helped the Vol. 2 team identify the names and meanings of various moves and entertained them with stories from the streetball canon and old times.

The Influence of Dr. Funk

Smith and Garcia’s perspective helped the Vancouver boys craft the essential identity of NBA Street Vol. 2. It collapsed basketball timelines, allowing modern NBA stars to play against old-school legends on the asphalt. But just as importantly, it challenged the NBA’s dominance by portraying the streetball court as the great equalizer that doesn’t care about labels like “pro” or “amateur.”

In this respect, the game is “Dr. Funk,” a three-part Nike campaign that Smith was a part of starting in 2001. A particularly perfect 60-second Dr. Funk spot occurs in the final seconds of a 1975 game at Rucker Park. The crowd screams for Dr. Funk over the radio. Vince “The crowd went wild when Dr. Funk Carter took the field. Harlem basketball legend and drug lord Pee Wee Kirkland handed the ball to Dr. Garcia, while Bobbitt Garcia stood on the sideline and commented under his breath. Funk threw it and hit a windmill alley-oop to give the Uptowners the win. Cue Bootsy Collins.

“I think the Nike Freestyle captured the core game experience we wanted to give players. It’s a surprising move, but very easy to execute and always fun,” Mauser said. “Dr. Funk is clearly expressing more of a cultural atmosphere and a direct experience that the audience should be immersed in. On the one hand, it was about combining the magic and awe of the athletes with an experience that is only possible in a few places in the world, such as Rucker Park.”

Dr. Funk highlights how Volume 2 capitalizes on New York’s reputation as the mecca of outdoor basketball, incorporating the city’s rich streetball history, Rucker as a source from which legends are born, and the mythical elements of oral history and eyewitness testimony from the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s, when the line between fable and fact became blurred. The physics in Volume 2 are reminiscent of the superhuman feats of former New York streetball kings like Earl “The Goat” Manigault, who (reportedly) could pick up a dollar bill off the top of the backboard and leave a ton of bills behind. Coyne; Herman “Helicopter” Knowings, who could (allegedly) shoot 720 flashes from the free throw line; Joe “The Destroyer” Hammond, who faced Julius Erving in a Rucker game and (actually) scored 50 points in the first half. This retro look at Ruckers for Vol. 2 starts in Harlem and culminates with a time slip to Ruckers ’78, battling the trio Dr. J, Connie Hawkins and Earl Monroe. Stretch Monroe became the game’s unofficial mascot, a doppelganger of Dr. J. Wearing the number 72, J was a lanky jumper and dunker extraordinaire from East Harlem who was little more than a phantom of basketball OG. Uptown was.

Making the Soundtrack

Moselle wanted a 100% hip-hop soundtrack for NBA Street, but ran into budgetary constraints that often hindered development of new series, so the music was primarily handled by in-house composers. That all changed with Vol. 2.

“The success of the first NBA Street gave us credibility and the freedom to do something relevant and impactful with the soundtrack,” Moselle explained. “Vol. 2 was about to be released, the NBA was finally ready to incorporate hip-hop into the video games they were involved in. ” “Reminisce Over You (T.R.O.Y.)” by Pete Rock and CL Smooth is the song that plays on the main menu and sets the tone for the entire game. Built around a majestic saxophone loop, “T.R.O.Y.” is a nostalgia in itself, dealing with intergenerational relationships, asserting a deep connection to the dead, and is here to define the Vols’ identity by looking back to the golden age. It’s a rare song that never really gets old.

“When you work on a project like this, you end up listening to the songs, especially the first one or two, tens of thousands of times because you keep turning the game on and off to make sure everything is working,” said Myhill. “And I never get tired of this track. I hear it in my head and it’s like a warm and fuzzy feeling. I’ve never had that with any other song in the game. I just wanted to punch myself in the face because it’s a song I’ve heard 400 times.”

Nelly performed with Clipse and Fabolous on a frosty autumn night in Vancouver during the Nellyville tour. After the show, Nelly and The Saint Lunatics went to the EA campus and “played NBA Street ’til we dropped.” Nelly promised to write exclusive songs for the soundtrack and Vol. The two designers rewarded the development of Not In My House by including all five St. Lunatics as unlockable characters in the game. (Inexplicably, Nelly’s personality is not as good as Slowdown’s.)

At one point, “Vol. 2” invited three advisors to the Vancouver campus: Just Blaze, the hottest producer in the world at the time, rapper Jensen “Hot Karl” Karp, and a pre-“Get Rich or Die Tryin’” 50 Cent. Canadian border officials denied 50 Cent entry due to his criminal history, and he immediately returned to New York on the next plane.

Karp recalls that at the time of the visit, the team had already developed a mood board with “New York streets, a kind of Rucker-based graphics.” In the meeting, he suggested “T.R.O.Y.” as the theme song for the game, and Just Blaze immediately approved this great idea. “Blaze was like, ‘Yeah, that’s crazy,’” Karp recalled.

Just Blaze got them into the studio to record an original beat for the game. “We spent a million dollars on the studio, which was a studio with no money,” Myhill said. “And he came in and rocked it. I’ve never seen anything like this before. He basically finished the song in a flash, like he got inspiration from somewhere.” It was a crazy, life-changing experience to see what this guy did.”

“It was always the story of the night before that actually inspired the track names,” Moselle said. “I’ll never forget that one song on the soundtrack, ‘Plan B,’ was born from something that happened last night.”

A Product of Its Time

Two more series came out in the NBA Street Series: V3 and Home Court. Though popular, they didn’t quite retain the intangible qualities and subtle details that made Vol. 2 so special: the Curtis Mayfield Superfly font, the old-school uniforms, and the use of old Blue Note album covers as the basis for the overall game color scheme. V3 moved away from the retro premise of Vol. 2 and moved closer to AND1 and the modern streetball aesthetic.

“I think the art style allowed us to break away from being completely believable,” Myhill said of Vol. 2. “We didn’t apply the street shading effect to the skin, so it looks a little less painterly or iconic and graphic. When the player moves really fast, it gets awful because we’re actually trying to add skin texture to make it look photorealistic.”

Like albums and movies, video games are the product of not only the participants but also a specific time and organic chemistry. It’s not something that can be easily replicated. The designers of Vol. 2 have since had successful careers at various companies in the video game industry, but they remain friends and now recall Vol. 2, a painstaking project that they say was a labor of love.

“We absolutely loved the product,” Gibbons said. “We loved it and lived it. We were young and we didn’t have families.”

I own both Vol. 2 and NBA 2K18, the quintessential basketball video game. Vol. 2 is the better game. Playing for 21 points in Vol. 2 brings a different vibe to 2K18 than playing in time-limited quarters, bringing a timeless, graceful, and fun playground innocence to the basketball game experience. Playing a 2K18 game is intense, immersive, and fun, but it doesn’t evoke the same joy. It’s much more likely to cause a heart attack. And while 2K18 manages to capture the precise movements and dynamics of an NBA game, and the idiosyncrasies of each player’s style, it’s ultimately an overproduced morass that tries to capture and save players through pre-game national anthems and in-studio halftime analysis. The main menu of 2K18 features a Kyrie Irving quote that reads, “Basketball isn’t a game. It’s an art form.” It’s the de facto tagline of a game that doesn’t take artistic liberties with itself, but rather tries to. It recreates the broadcast experience as faithfully as possible.

“Traditional sports games are going to be televised,” Moselle said. “It’s a hectic experience. It’s produced this way. And what’s really interesting is that even 15 years ago, one of our tenets was to be against transference. But we had to create our own vocabulary and our own visual presentation that didn’t look like television, and we could be on the court and keep the ball in our hands.”

It’s also a big part of Vol. 2 predates the connection between consoles and the internet. It’s both a blessing and a curse that 2K18 and most modern sports games adhere to the slavish realism made possible by the internet. If in the real world John Wall is out for arthroscopic knee surgery, the game will feature Thomas Satlanczy as your point guard. By avoiding 2K18 and opting for Vol. 2 instead, you can escape the oppression of Satlanczy and relive a simpler time in life and video game technology.

For me, a lonely Sonics fan, Vol. 2 is a chance to relive the sublime era when Vladimir Radmanovic roamed the floor. I couldn’t fully appreciate it then, but listening to it now makes me appreciate it. It was presented in my digital age, restless in sound, overwhelming in emotion. Vol. 2 has indeed changed – it’s no longer old school vs. new school, it’s old school vs. Old school. More nostalgia. 15 years later, it’s still fresh and addictive. It’s the feeling you get when Radmanovic breaks back-to-back opponents’ ankles before floating up to the basket in a honey-dip of victory. A purer expression of the joy and expressive elements of basketball has never been made before, and probably never will be.

Leave a Reply